To Chile and back – a journey through history

May 30, 1962. Chile. A landmark date and place in the annals of Bulgarian sports. The national football team is set to play its first-ever World Cup match. The game between Bulgaria and Argentina was scheduled to take place in the town of Valdivia, which, alas, history had destined for a very different fate. On May 22, 1960, at 15:11 local time, Valdivia became the epicenter of the strongest recorded earthquake in human history – a magnitude 9.6 on the Richter scale. The Pacific town, located about 700 km from the capital Santiago, was completely destroyed.

To save the World Cup, the Chilean government turned to the American mining company Braden, which had built a small stadium for 14,000 spectators in the town of Rancagua. This allowed the hosts to organize the Jules Rimet Cup tournament across four stadiums: in Santiago, Rancagua, Viña del Mar, and Arica.

Legend has it that the Chilean disaster and the World Cup were cursed by… Argentina. After two consecutive tournaments in Europe, the South American federations threatened a full boycott if the competition was not held on their continent. The absolute favorite was Argentina, which had not yet hosted the most important football forum.

The president of the Argentine federation, Raúl Colombo, concluded his speech at the Lisbon congress in 1956 with: “We can start the tournament tomorrow. We have everything!” With this, he highlighted the strongest point of his candidacy – the modern stadiums, developed infrastructure, and the country’s football prestige.

He was followed by the president of the Chilean federation, Dittborn, who said: “We have nothing. And precisely for that reason, we want this tournament!” Chile won 31 votes against 10 for Argentina. Fourteen federations abstained. The government, football association, and civil society in Buenos Aires were outraged, and Chile was publicly “cursed to remain forever with nothing.”

The 1962 World Cup featured 16 teams, with only eight spots allocated to Europe. Bulgaria and France finished their qualifying group with the same number of points, which required a playoff match on neutral ground. On December 16, 1961, at San Siro in Milan, the Bulgarians won with a goal by Dimitar Yakimov. This marked the first time in their history that the “Lions” qualified for the finals of the Jules Rimet Cup.

The 1962 World Cup in Chile is remembered as the roughest and bloodiest tournament in World Cup history. One of the most infamous matches was between the hosts and Italy, known as the “Battle of Santiago.” Players from both teams continuously kicked and fought each other, with police, fans, and officials joining in the frequent brawls. Many were carried off on stretchers, and some suffered broken noses. Elsewhere on the pitch, similar violence occurred: a Soviet defender was carried off unconscious with a broken leg after a brutal tackle from a Yugoslav player, and a Swiss player suffered the same fate. Chile and West Germany chased each other across the field exchanging punches, and even Pelé was not spared—he was repeatedly fouled by Czechoslovak defenders and taken out of the group stage.

However, the tournament also saw the rise of the incomparable Mané Garrincha, who dazzled on the pitch. In the semifinals, the Brazilian virtuoso, frustrated by constant fouls from Chilean players, literally knocked out defender Rojas and was sent off. Interestingly, red cards had not yet been introduced at this World Cup; referees dismissed offenders with hand gestures. Not all referees commanded authority, so at times, the role of enforcement fell to the police.

The Bulgarian team, led by Georgi Pachedzhiev and Krastyo Chakarov, traveled to the mining town of Mahali, where they trained on the pitches in the public park. In contrast, the English team, also in Bulgaria’s group, stayed at the headquarters of the Braden mining company in Rancagua. The “Tricolor” squad was the only team at the World Cup with three youth players—Dobromir Zhechev, Georgi Sokolov, and Georgi Asparuhov—while most other teams didn’t have any. Gundi was the second youngest player at the finals, with only the Brazilian Coutinho being younger.

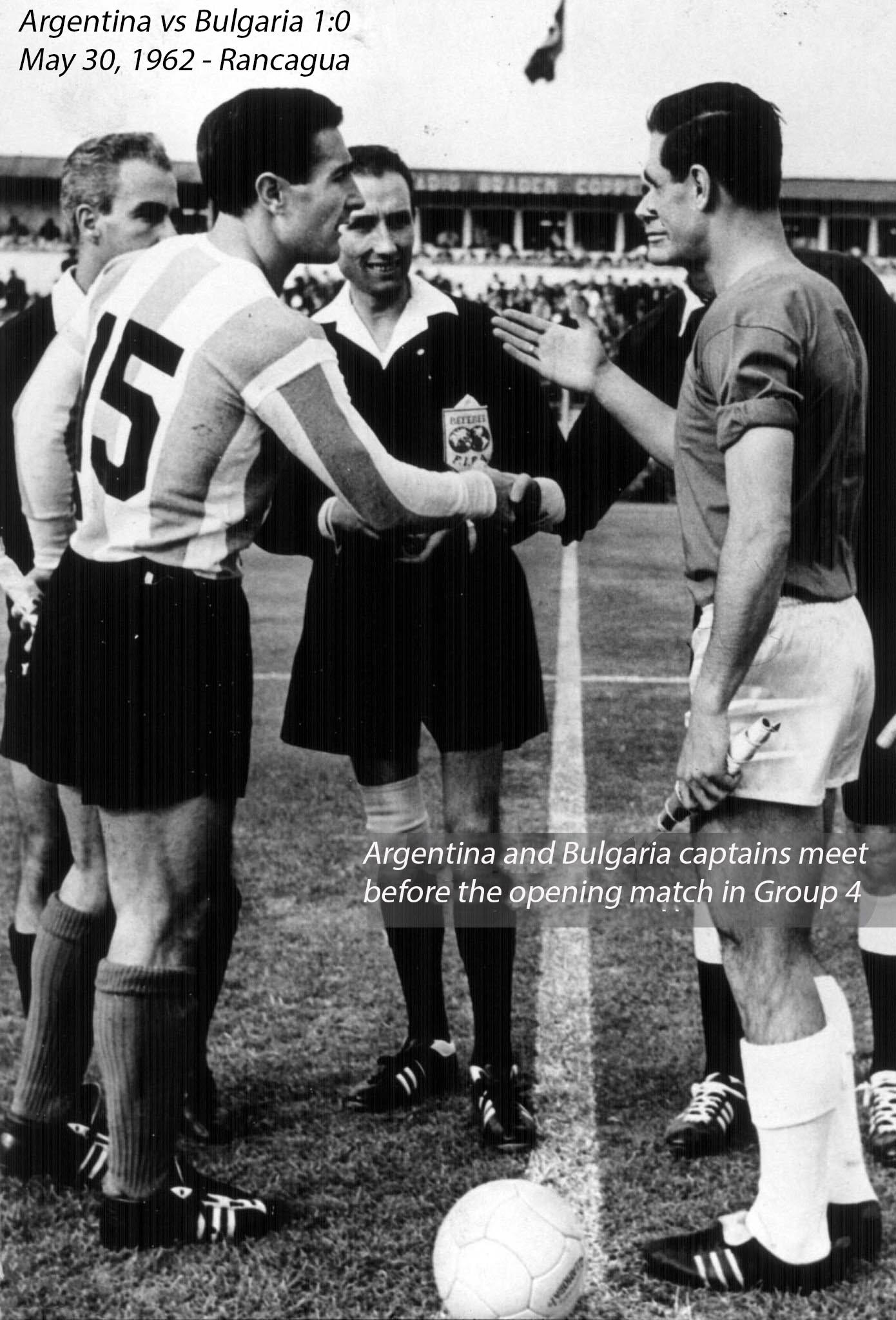

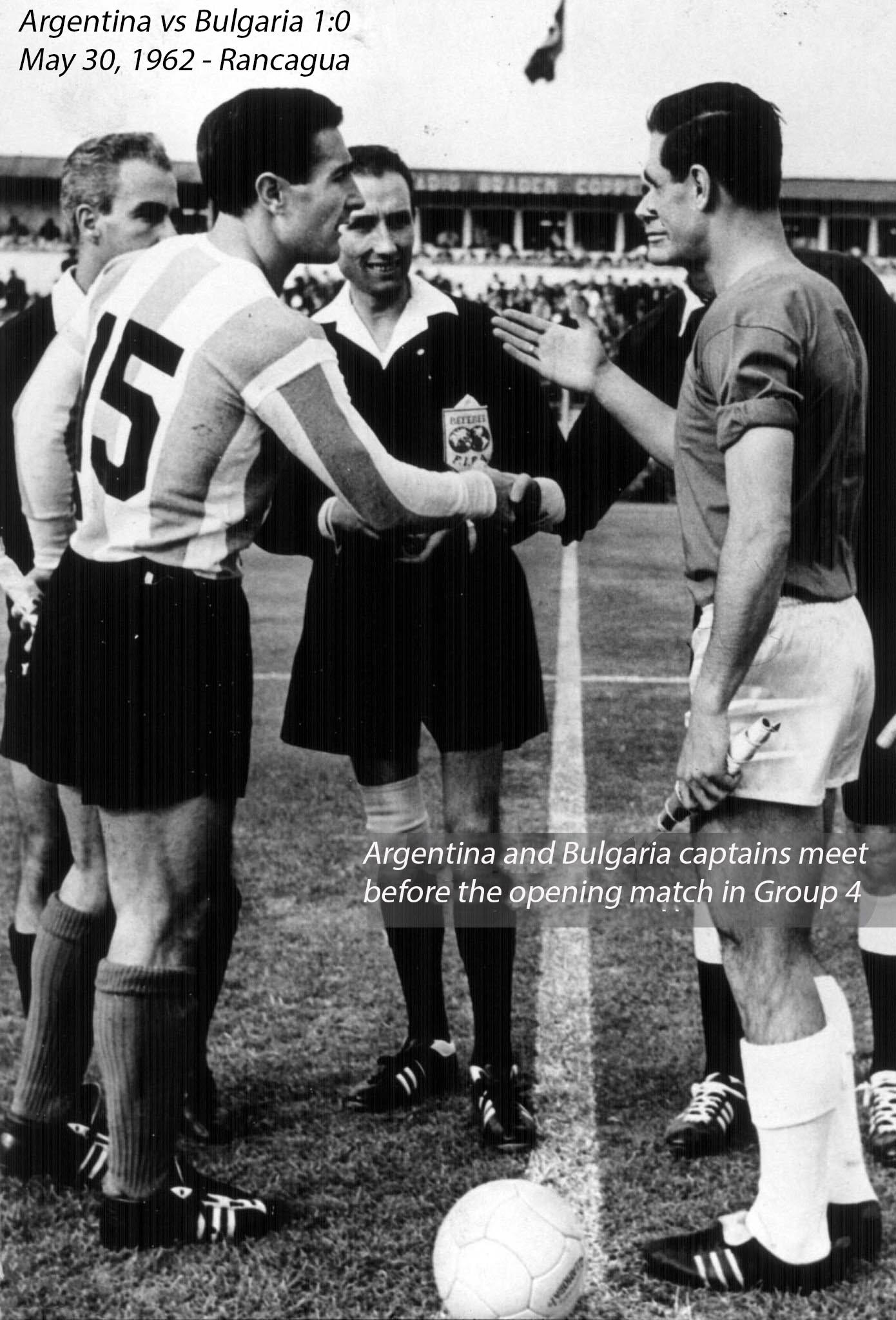

On May 30, 1962, Bulgaria and Argentina played the opening match of the World Cup in their group. In fact, on the opening day, four matches were played simultaneously, one from each group. Bulgaria’s starting lineup for the match against the “Gauchos” at Estadio Braden in Rancagua was as follows: Georgi Naydenov, Kiril Rakarov, Ivan Dimitrov, Stoyan Kitov, Dimitar Kostov, Nikola Kovachev, Todor Diev, Petar Velichkov, Hristo Iliev, Dimitar Yakimov, and Ivan Kolev.

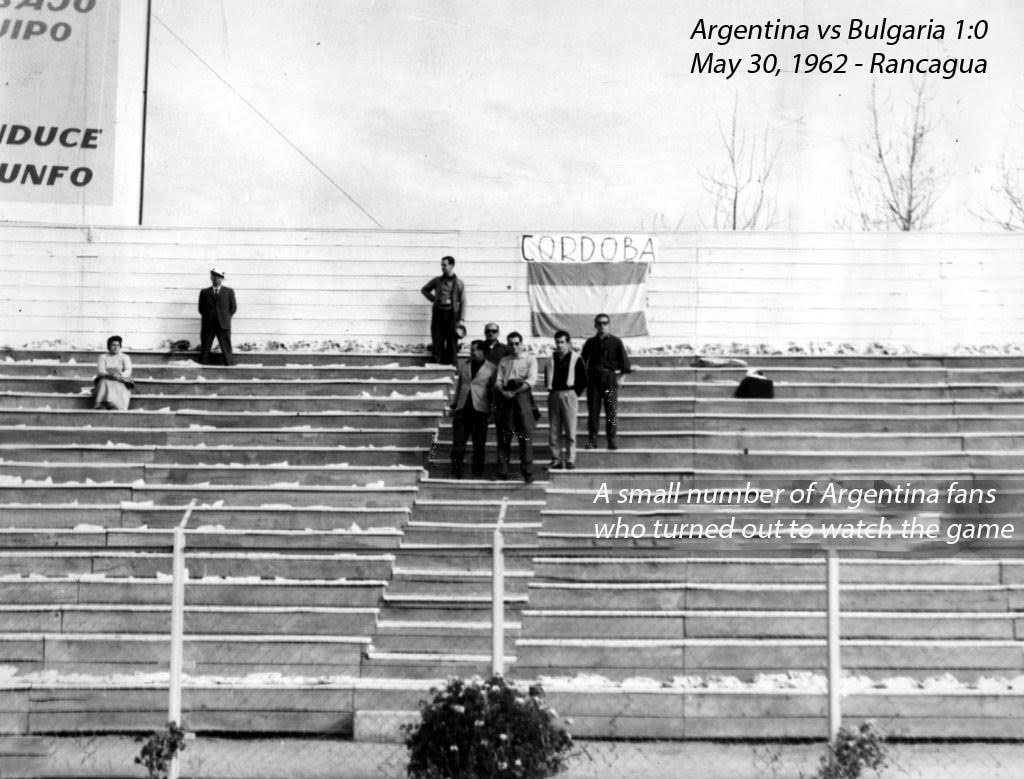

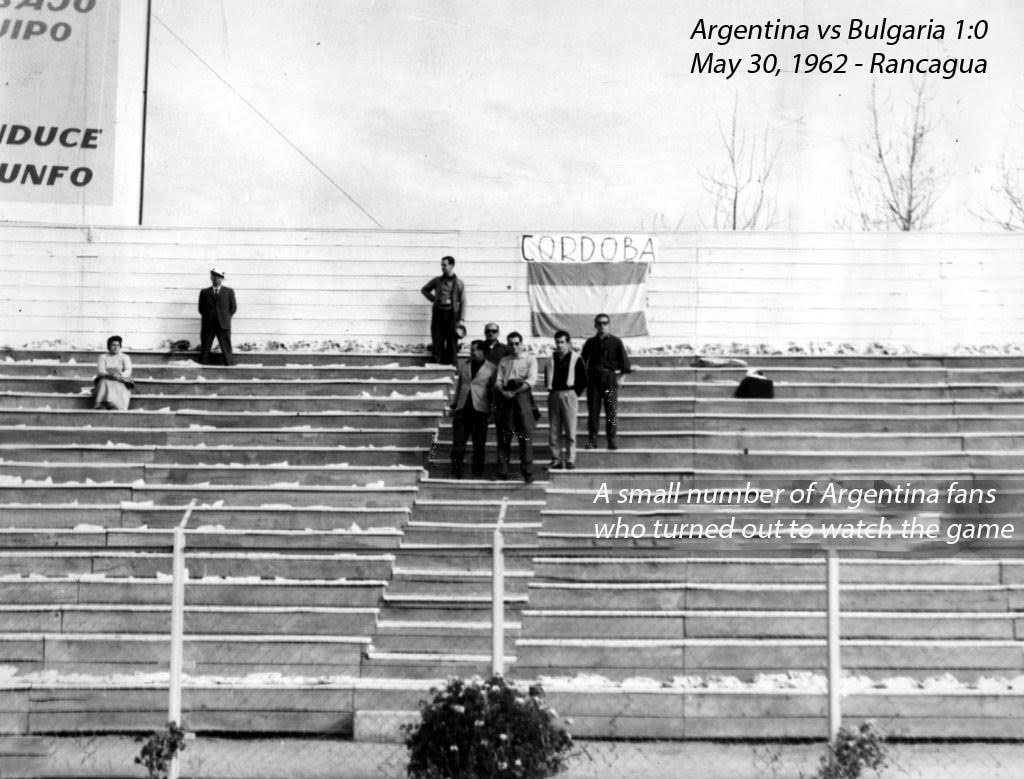

Everything is decided as early as the fourth minute, when Facundo scores against us. Our team tries to attack but very rarely threatens the opposing goal, and the match is played entirely in the rough style typical of the tournament, with constant tackles and fouls. The Argentinians injure two of our starters. Of course, there isn’t a single Bulgarian fan in the stands— all 7,134 spectators are supporting Argentina.

The second match of the tournament, on June 3, again in Rancagua, starts horrifically. Hungary scores 4 goals against us in the first 12 minutes. At halftime, in the locker room, the leadership of the Bulgarian delegation in Chile erupts in a fierce scandal and orders the team to turn the score around. The “horsepower” approach has little effect, and the Hungarians score a fifth goal. This is when 19-year-old Georgi Asparuhov – Gundi – makes his entrance. He goes down in history with Bulgaria’s first goal at a World Cup. A curious incident accompanies the goal, as it is officially credited to Georgi Sokolov, and it still appears that way in FIFA’s archives. The two Georgis had exchanged jerseys, which caused confusion among the match delegates. The matches were not broadcast on television in Bulgaria. The game against the Hungarians ends 6:1.

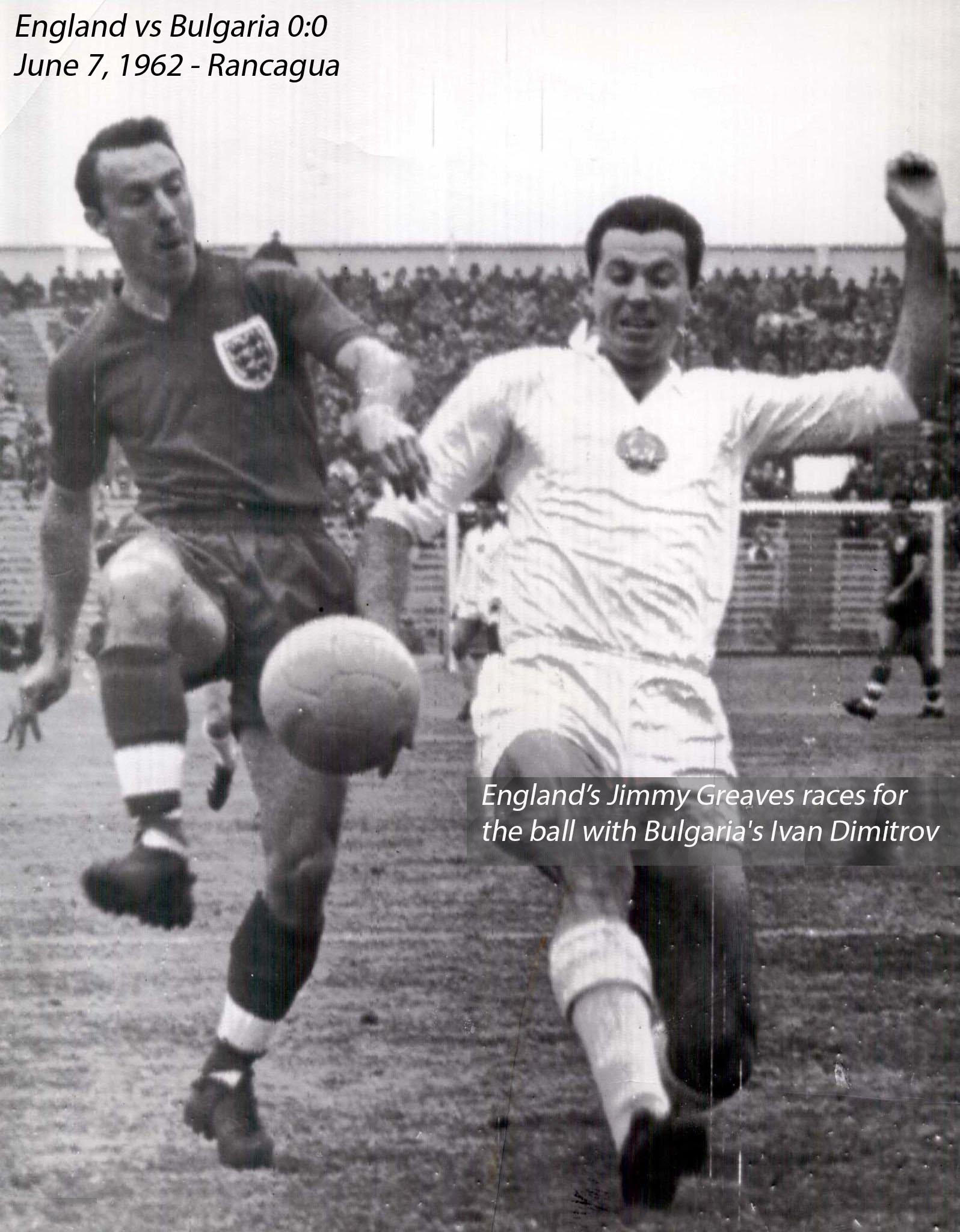

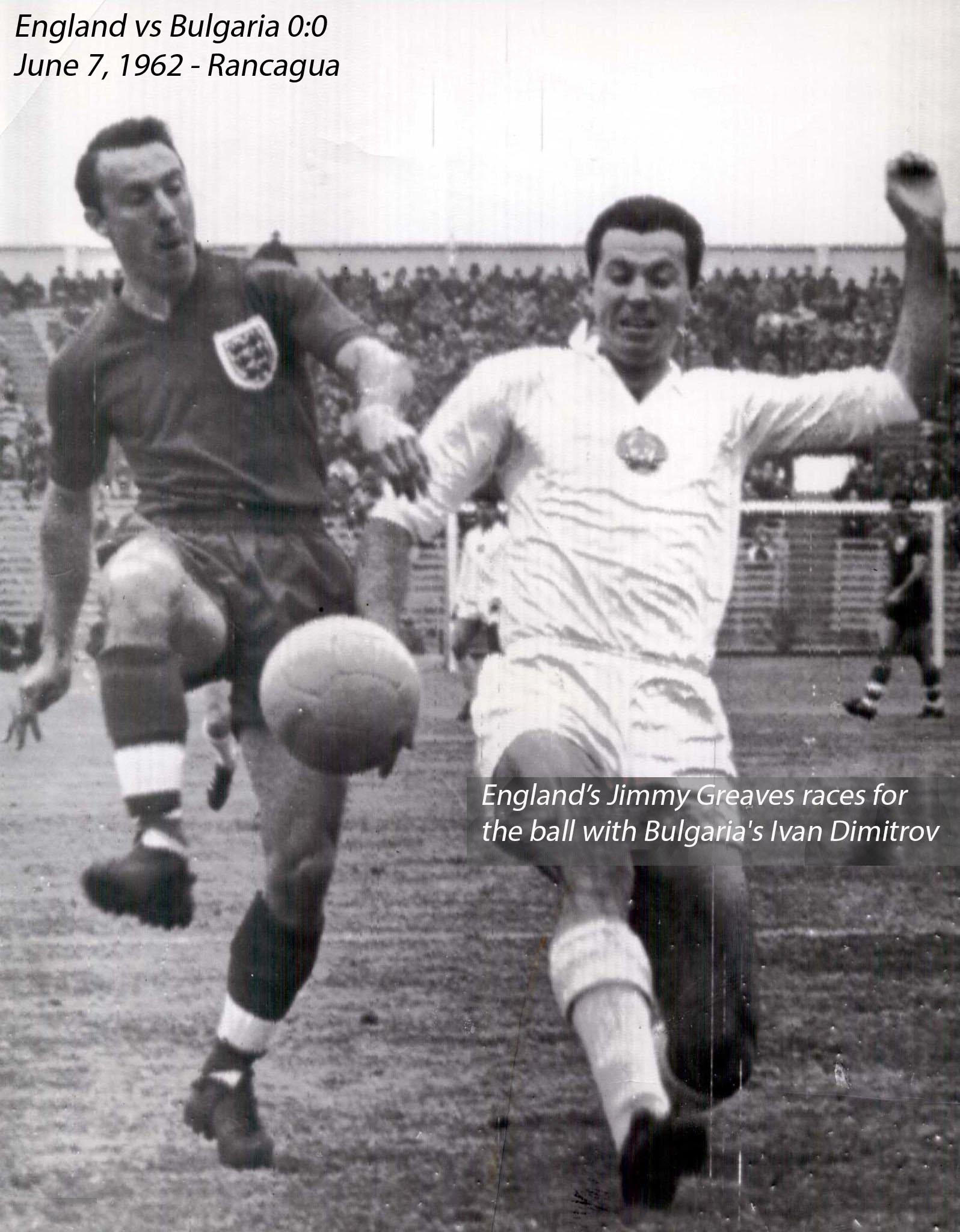

Our final match at the World Cup is largely ceremonial, but we manage to register our first (partial) positive result – a 0:0 draw against England. The Bulgarian team plays well, and Gundi’s powerful shot even rattles the crossbar. Thus ends Bulgaria’s first adventure on football’s biggest stage.

Estadio “Braden” in Rancagua is the smallest stadium of the World Cup. Around 6,000–7,000 spectators attended Bulgaria’s matches against Argentina, Hungary, and England, making it the lowest attendance of the tournament—tied, curiously, with the semifinal between Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia held in Viña del Mar (5,890 spectators). Tickets from these four matches are correspondingly the rarest and most sought-after by collectors.

In the Bulgarian Football Shirts collection, we preserve the original tickets from the debut matches of the Bulgarian national team at the World Cup in Chile.

May 30, 1962. Chile. A landmark date and place in the annals of Bulgarian sports. The national football team is set to play its first-ever World Cup match. The game between Bulgaria and Argentina was scheduled to take place in the town of Valdivia, which, alas, history had destined for a very different fate. On May 22, 1960, at 15:11 local time, Valdivia became the epicenter of the strongest recorded earthquake in human history – a magnitude 9.6 on the Richter scale. The Pacific town, located about 700 km from the capital Santiago, was completely destroyed.

To save the World Cup, the Chilean government turned to the American mining company Braden, which had built a small stadium for 14,000 spectators in the town of Rancagua. This allowed the hosts to organize the Jules Rimet Cup tournament across four stadiums: in Santiago, Rancagua, Viña del Mar, and Arica.

Legend has it that the Chilean disaster and the World Cup were cursed by… Argentina. After two consecutive tournaments in Europe, the South American federations threatened a full boycott if the competition was not held on their continent. The absolute favorite was Argentina, which had not yet hosted the most important football forum.

The president of the Argentine federation, Raúl Colombo, concluded his speech at the Lisbon congress in 1956 with: “We can start the tournament tomorrow. We have everything!” With this, he highlighted the strongest point of his candidacy – the modern stadiums, developed infrastructure, and the country’s football prestige.

He was followed by the president of the Chilean federation, Dittborn, who said: “We have nothing. And precisely for that reason, we want this tournament!” Chile won 31 votes against 10 for Argentina. Fourteen federations abstained. The government, football association, and civil society in Buenos Aires were outraged, and Chile was publicly “cursed to remain forever with nothing.”

The 1962 World Cup featured 16 teams, with only eight spots allocated to Europe. Bulgaria and France finished their qualifying group with the same number of points, which required a playoff match on neutral ground. On December 16, 1961, at San Siro in Milan, the Bulgarians won with a goal by Dimitar Yakimov. This marked the first time in their history that the “Lions” qualified for the finals of the Jules Rimet Cup.

The 1962 World Cup in Chile is remembered as the roughest and bloodiest tournament in World Cup history. One of the most infamous matches was between the hosts and Italy, known as the “Battle of Santiago.” Players from both teams continuously kicked and fought each other, with police, fans, and officials joining in the frequent brawls. Many were carried off on stretchers, and some suffered broken noses. Elsewhere on the pitch, similar violence occurred: a Soviet defender was carried off unconscious with a broken leg after a brutal tackle from a Yugoslav player, and a Swiss player suffered the same fate. Chile and West Germany chased each other across the field exchanging punches, and even Pelé was not spared—he was repeatedly fouled by Czechoslovak defenders and taken out of the group stage.

However, the tournament also saw the rise of the incomparable Mané Garrincha, who dazzled on the pitch. In the semifinals, the Brazilian virtuoso, frustrated by constant fouls from Chilean players, literally knocked out defender Rojas and was sent off. Interestingly, red cards had not yet been introduced at this World Cup; referees dismissed offenders with hand gestures. Not all referees commanded authority, so at times, the role of enforcement fell to the police.

The Bulgarian team, led by Georgi Pachedzhiev and Krastyo Chakarov, traveled to the mining town of Mahali, where they trained on the pitches in the public park. In contrast, the English team, also in Bulgaria’s group, stayed at the headquarters of the Braden mining company in Rancagua. The “Tricolor” squad was the only team at the World Cup with three youth players—Dobromir Zhechev, Georgi Sokolov, and Georgi Asparuhov—while most other teams didn’t have any. Gundi was the second youngest player at the finals, with only the Brazilian Coutinho being younger.

On May 30, 1962, Bulgaria and Argentina played the opening match of the World Cup in their group. In fact, on the opening day, four matches were played simultaneously, one from each group. Bulgaria’s starting lineup for the match against the “Gauchos” at Estadio Braden in Rancagua was as follows: Georgi Naydenov, Kiril Rakarov, Ivan Dimitrov, Stoyan Kitov, Dimitar Kostov, Nikola Kovachev, Todor Diev, Petar Velichkov, Hristo Iliev, Dimitar Yakimov, and Ivan Kolev.

Everything is decided as early as the fourth minute, when Facundo scores against us. Our team tries to attack but very rarely threatens the opposing goal, and the match is played entirely in the rough style typical of the tournament, with constant tackles and fouls. The Argentinians injure two of our starters. Of course, there isn’t a single Bulgarian fan in the stands— all 7,134 spectators are supporting Argentina.

The second match of the tournament, on June 3, again in Rancagua, starts horrifically. Hungary scores 4 goals against us in the first 12 minutes. At halftime, in the locker room, the leadership of the Bulgarian delegation in Chile erupts in a fierce scandal and orders the team to turn the score around. The “horsepower” approach has little effect, and the Hungarians score a fifth goal. This is when 19-year-old Georgi Asparuhov – Gundi – makes his entrance. He goes down in history with Bulgaria’s first goal at a World Cup. A curious incident accompanies the goal, as it is officially credited to Georgi Sokolov, and it still appears that way in FIFA’s archives. The two Georgis had exchanged jerseys, which caused confusion among the match delegates. The matches were not broadcast on television in Bulgaria. The game against the Hungarians ends 6:1.

Our final match at the World Cup is largely ceremonial, but we manage to register our first (partial) positive result – a 0:0 draw against England. The Bulgarian team plays well, and Gundi’s powerful shot even rattles the crossbar. Thus ends Bulgaria’s first adventure on football’s biggest stage.

Estadio “Braden” in Rancagua is the smallest stadium of the World Cup. Around 6,000–7,000 spectators attended Bulgaria’s matches against Argentina, Hungary, and England, making it the lowest attendance of the tournament—tied, curiously, with the semifinal between Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia held in Viña del Mar (5,890 spectators). Tickets from these four matches are correspondingly the rarest and most sought-after by collectors.

In the Bulgarian Football Shirts collection, we preserve the original tickets from the debut matches of the Bulgarian national team at the World Cup in Chile.